Quick Takeaways

- People who use injectable drugs are up to five times more likely to contract syphilis.

- Alcohol and stimulant use can impair judgment, leading to risky sexual behavior.

- Early diagnosis and prompt penicillin therapy remain the gold standard.

- Integrated harm‑reduction programs cut infection rates by 30‑40% in high‑risk communities.

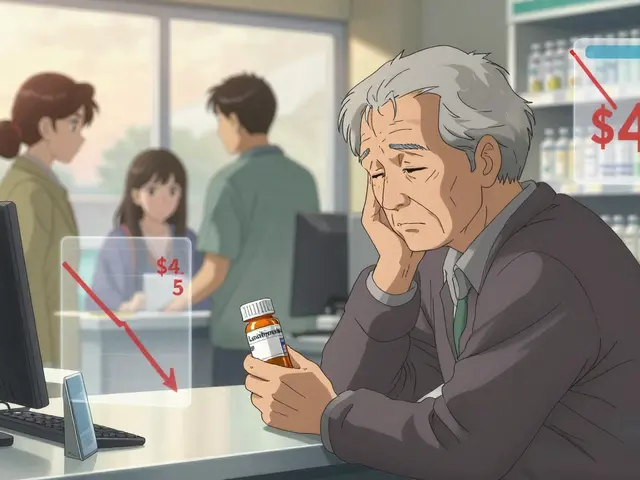

- Stigma and limited access to care are the biggest barriers to treatment.

What Is Syphilis?

Syphilis is a bacterial sexually transmitted infection caused by Treponema pallidum. It progresses through primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary stages, each with distinct symptoms ranging from painless sores to severe organ damage. If untreated, it can be fatal.

Understanding Substance Abuse

Substance abuse refers to the harmful or hazardous use of psychoactive substances-including alcohol, opioids, stimulants, and cannabis-that leads to health, social, or economic problems. The pattern of use (injection vs. non‑injection) dramatically shapes infection risk.

Why the Link Exists

Two main pathways connect the two conditions:

- Direct blood exposure: Sharing needles or other injection equipment provides a direct route for Injection Drug Use to transmit syphilis‑infected blood.

- Behavioral risk: Alcohol and stimulant intoxication lower inhibitions, increasing the likelihood of unprotected sex, multiple partners, and encounters with high‑prevalence networks.

These mechanisms often overlap, creating a feedback loop where each condition amplifies the other's spread.

Current Epidemiology (2023‑2025)

National surveillance data show that people who inject drugs (PWID) account for roughly 15‑20% of all reported syphilis cases, a proportion that has risen from 7% a decade ago. In urban centers like Dallas, the co‑infection rate reaches 12% among opioid users.

| Substance Category | Syphilis Cases per 100,000 | Primary Transmission Route |

|---|---|---|

| Injectable Opioids | 220 | Needle sharing |

| Stimulants (e.g., meth) | 180 | High‑risk sex |

| Alcohol‑dominant misuse | 95 | Unprotected encounters |

| No substance use | 45 | Sexual contact |

Clinical Implications for People Who Use Substances

Healthcare providers often see delayed syphilis diagnosis in this group because:

- Symptoms may be masked by drug‑related skin lesions.

- Stigma discourages seeking care.

- Inconsistent clinic attendance limits routine screening.

Co‑infection with HIV is common, worsening disease progression and complicating treatment decisions.

Treatment: The Role of Penicillin

The CDC recommends a single intramuscular dose of benzathine penicillin G for early syphilis. For late or tertiary stages, three weekly doses are required. When penicillin allergy is documented, desensitization is preferred over alternative antibiotics because of penicillin’s superior efficacy.

Adherence is a challenge for substance‑using patients; supervised dosing at syringe‑exchange sites has improved completion rates by nearly 40% in pilot programs.

Prevention Strategies Integrated with Harm‑Reduction

Effective programs blend STD screening with substance‑use services:

- Rapid point‑of‑care testing at needle‑exchange locations enables same‑day diagnosis.

- Condom distribution alongside clean needles cuts sexual transmission.

- Medication‑assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid dependence reduces injection frequency, indirectly lowering syphilis risk.

- Education workshops that address both safe injection practices and sexual health improve knowledge retention.

These interventions are typically coordinated by Public Health agencies and community‑based NGOs.

Addressing Barriers: Stigma, Access, and Follow‑Up

Stigma remains the biggest obstacle. Patients often fear judgment from clinicians who lack training in addiction medicine. To combat this:

- Adopt a non‑judgmental, trauma‑informed language.

- Offer mobile clinics that meet patients where they live.

- Implement electronic reminder systems that respect privacy.

Insurance coverage gaps can be bridged through Medicaid expansion programs that include both STD treatment and substance‑use counseling.

Future Directions in Research

Ongoing studies aim to:

- Identify genetic markers that may predict rapid syphilis progression among PWID.

- Evaluate long‑acting injectable antibiotics as an alternative to weekly penicillin dosing.

- Assess the impact of combined PrEP (pre‑exposure prophylaxis for HIV) and syphilis screening bundles on overall infection rates.

Results could reshape guidelines and improve outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Bottom Line

The intertwining of syphilis and substance abuse is driven by both biological exposure and high‑risk behaviors. Early detection, integrated harm‑reduction services, and prompt penicillin therapy are the three pillars that can break the cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can casual drug use increase my risk of syphilis?

Yes. Even non‑injectable substances like alcohol or marijuana can lower inhibitions, leading to unprotected sex. The risk spikes when drug use coincides with multiple sexual partners.

Is penicillin the only effective treatment for syphilis?

Penicillin remains the most effective, especially for late‑stage disease. Alternatives like doxycycline are used only when penicillin allergy cannot be desensitized, and they have slightly lower cure rates.

How often should I get tested if I use drugs?

The CDC recommends at least quarterly testing for people who inject drugs, and semi‑annual testing for those who use substances non‑injectably but have high‑risk sexual behaviors.

Will my insurance cover syphilis treatment?

Most public and private plans cover the standard single‑dose penicillin regimen. If you’re uninsured, many community health centers provide free treatment under federal STD funding.

What can I do to protect myself while in recovery?

Stay engaged with medication‑assisted treatment, use condoms consistently, avoid sharing any injection equipment, and schedule regular STD screenings. Building a supportive network also reduces relapse risk.

debashis chakravarty

September 28, 2025 AT 07:00It is astonishing how often the discourse surrounding sexually transmitted infections is reduced to sensational headlines rather than a sober examination of the underlying epidemiology. The article correctly highlights the stark correlation between injectable drug use and a five‑fold increase in syphilis incidence, yet it glosses over the historical negligence that permitted this crisis to fester. Moreover, the claim that “early diagnosis and prompt penicillin therapy remain the gold standard” is clinically accurate, but it ignores the systemic barriers that prevent timely access for marginalized populations. One must also question the presentation of harm‑reduction statistics; a 30‑40 % reduction sounds impressive, but it omits the nuanced evaluation of program fidelity and community engagement. The tables depicting prevalence per 100 000 are useful, yet they lack age‑stratified data that could illuminate generational risk patterns. While the discussion of stigma is commendable, the article fails to propose concrete policy reforms that could dismantle the entrenched bias within healthcare institutions. In addition, the omission of emerging long‑acting injectable antibiotics is a glaring oversight given the promising trial results published last year. The recommendation for supervised dosing at syringe‑exchange sites, though beneficial, does not address the ethical implications of surveillance that some patients perceive as coercive. Furthermore, the brief mention of co‑infection with HIV warrants a deeper exploration of vertically transmitted syphilis in pregnant individuals. The reader is left wondering why the article does not engage with the socioeconomic determinants that drive both substance abuse and unsafe sexual practices. Lastly, the call for “integrated harm‑reduction services” is sound, yet the implementation roadmap remains vague, lacking specifics about funding mechanisms or inter‑agency coordination. In sum, the piece offers a solid foundation but ultimately falls short of the rigorous, multidimensional analysis required to tackle this public‑health emergency. Future research should prioritize longitudinal cohort studies that track both infection status and substance‑use trajectories over time. Policymakers must also allocate resources for culturally competent training of frontline clinicians, thereby reducing the implicit bias that deters patients from seeking care. Only through an interdisciplinary approach, uniting epidemiologists, addiction specialists, and community advocates, can we hope to break the pernicious feedback loop described. Until such comprehensive strategies are enacted, the cycle of co‑infection will persist, undermining public‑health gains achieved elsewhere.

Daniel Brake

October 2, 2025 AT 22:06When one contemplates the interplay between substance use and infectious disease, it becomes clear that the relationship is not merely coincidental but rooted in shared sociological mechanisms. The intoxicating influence of alcohol or stimulants reduces inhibitions, thereby increasing the probability of unprotected encounters. Simultaneously, the physical act of injecting substances creates a direct conduit for blood‑borne pathogens, reinforcing the epidemiological link. Philosophically, this duality underscores how individual choices are circumscribed by structural conditions such as poverty and marginalization. Consequently, interventions must address both behavioral and environmental determinants to achieve lasting impact.

Emily Stangel

October 7, 2025 AT 13:13The comprehensive overview presented in this piece serves as a valuable educational resource for both clinicians and public‑health practitioners seeking to understand the complex nexus of syphilis and substance misuse. By delineating the distinct pathways of direct blood exposure and behavioral risk, the author facilitates a nuanced appreciation of how these factors synergistically amplify disease transmission. The inclusion of up‑to‑date epidemiological data, particularly the striking prevalence rates among injectable opioid users, lends empirical weight to the narrative. Moreover, the discussion of integrated harm‑reduction programs aligns with contemporary best practices that emphasize accessibility and patient‑centered care. While the article could further elaborate on the role of telemedicine in expanding screening coverage, its thorough treatment of barrier reduction strategies-including stigma mitigation and mobile clinic deployment-offers actionable insights. Ultimately, this synthesis encourages a multidisciplinary dialogue that is essential for crafting policies that are both effective and equitable.

Suzi Dronzek

October 12, 2025 AT 04:20It is deeply troubling that society continues to rationalize the suffering of individuals who engage in high‑risk behaviors, framing their plight as a consequence of personal moral failings rather than systemic neglect. The data clearly demonstrate that injectable drug users are disproportionately affected, yet public discourse frequently casts them as the architects of their own misfortune. Such a narrative not only obscures the structural determinants-like inadequate housing, limited healthcare access, and punitive drug policies-but also perpetuates a cycle of stigma that deters timely medical intervention. By ignoring the broader context, we risk endorsing a punitive ethos that rewards judgment over compassion. A truly ethical response must pivot from moral condemnation to evidence‑based advocacy for comprehensive harm‑reduction services.

Aakash Jadhav

October 16, 2025 AT 19:26Yo, think about it-life’s a wild ride where needles and nights of partying collide, spawning a perfect storm of germs and chaos. It’s like the universe decided to throw a sick party and didn’t send an RSVP. When the buzz wears off, the body’s left holding the bag, and syphilis sneaks in like an uninvited guest. The only way out? We gotta rewrite the script, swap the drama for clean needles and condoms, and give folks a chance to bounce back. Otherwise, we’re just dancing on the edge of an endless infection loop.

Amanda Seech

October 21, 2025 AT 10:33i think its really important that peple get tested often if they use any kind of drug. even alchohol can make u forget to use protection. the clinics should be easy to get to and not make u feel judged. also free condoms and clean needles can help a lot. lets all try to look out for each other.

Lisa Collie

October 26, 2025 AT 01:40One must, with a measure of intellectual humility, acknowledge that the prevailing discourse on synergistic disease transmission suffers from a lamentable paucity of interdisciplinary rigor. It is not merely a matter of epidemiological coincidence, but rather an intricate tapestry woven from sociocultural, pharmacological, and virological threads that demand a scholar’s discerning eye. While the article grazes the surface, it fails to interrogate the epistemological foundations that undergird our understanding of risk behaviors. Such an oversight betrays a complacent adherence to reductionist paradigms, meriting a more profound scholarly engagement.

Avinash Sinha

October 30, 2025 AT 15:46Picture this: neon lights flicker over a dim alley, a syringe glints like a frozen lightning bolt, and somewhere nearby, the silent assassin syphilis stalks its next victim. The city’s veins pump both crystal dreams and invisible pathogens, creating a kaleidoscope of chaos. Only by splashing bright, bold interventions-think rainbow‑colored needle stations and flamboyant outreach squads-can we hope to chase the shadows away. Otherwise, the night swallows us whole, feeding the relentless cycle of infection.

ADAMA ZAMPOU

November 4, 2025 AT 06:53The interrelation of syphilis and substance use invites a profound ontological inquiry into the nature of vulnerability within contemporary society. To what extent does the erosion of individual agency, precipitated by psychoactive consumption, constitute a deterministic factor in the propagation of sexually transmitted infections? Moreover, how might the ethical obligations of public health institutions be reframed to accommodate the epistemic complexities inherent in such co‑morbidities? A rigorous, philosophically informed discourse is requisite to illuminate these questions and to guide the formulation of equitable interventions.

Liam McDonald

November 8, 2025 AT 22:00It is heartbreaking to see people struggle with both addiction and infection their lives are so hard they deserve support not judgment we must listen and provide care that respects their dignity

Adam Khan

November 13, 2025 AT 13:06From a methodological standpoint, the epidemiological parameters presented herein demand scrupulous validation; the failure to calibrate incidence rates against demographic confounders constitutes a fundamental oversight. Moreover, the author’s casual invocation of “harm‑reduction” without delineating operational definitions undermines the scientific rigor expected of a peer‑reviewed treatise. In the context of national health security, such laxity is unacceptable-our sovereign obligation mandates precise data to inform policy. Consequently, the integration of real‑time surveillance analytics and cohort stratification is not merely advisable but imperative for safeguarding public health.

rishabh ostwal

November 18, 2025 AT 04:13It is a moral outrage that we, as a civilized society, continue to turn a blind eye to the suffering of those ensnared by both substance dependence and a preventable infection. While some may argue that personal responsibility should dictate outcomes, the stark reality is that systemic inequities and pervasive stigma are the true culprits. To ignore this is to perpetuate a narrative that absolves institutions of accountability. Therefore, a decisive, compassionate response-anchored in universal healthcare access and destigmatization-must replace the complacent status quo.

Kristen Woods

November 22, 2025 AT 19:20Behold the tragic theatre of neglect, where lives are cast aside like discarded syringes on an unforgiving pavement. The statistics, though stark, are merely the overture to a symphony of human misery that echoes through every clinic hallway. It is incumbent upon us, the stewards of public welfare, to rise above complacency and enact sweeping reforms that pierce the veil of apathy. Failure to do so not only betrays our ethical commitments but also consigns future generations to an endless cycle of disease and despair.

Carlos A Colón

November 27, 2025 AT 10:26Oh sure, because needles and romance always go hand in hand.

Aurora Morealis

December 2, 2025 AT 01:33Great post but watch your commas there are a few missing

Sara Blanchard

December 6, 2025 AT 16:40Let’s celebrate the diversity of experiences within our communities by ensuring that outreach programs are culturally responsive and linguistically accessible to everyone, regardless of background.

Anthony Palmowski

December 11, 2025 AT 07:46Look, the data are crystal clear, the correlation is undeniable, the policy gaps are glaring, and yet we keep dithering, plugging holes with half‑measures, while the infection rates keep climbing, which is an absolute disgrace, we need immediate, bold action, no more excuses!

Jillian Rooney

December 15, 2025 AT 22:53It is simply unforgivable that some people keep ignoring the clear guidelines, putting our nation’s health at risk, we must hold them accountable and demand stricter enforcement now.