When you pick up a generic pill, you assume it works just like the brand-name version. That’s the whole point of bioequivalence - it’s the legal and scientific promise that the generic delivers the same medicine to your body at the same rate. But what if the batch of generic you’re holding isn’t even close to the batch used in the study that proved it was "equivalent"? That’s not a hypothetical. It’s happening right now, and the system isn’t built to catch it.

How Bioequivalence Is Measured (And Why It’s Flawed)

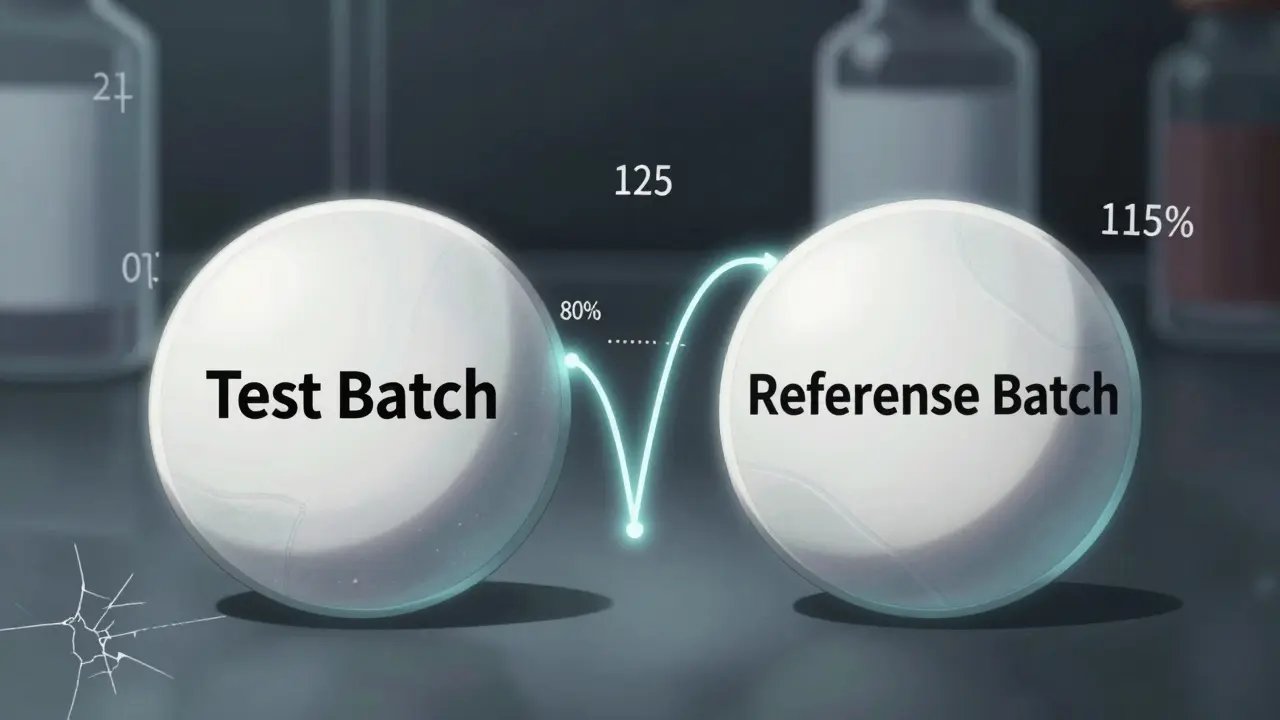

The standard way to prove a generic drug is bioequivalent to the brand name is simple: compare two numbers - the area under the curve (AUC) and the maximum concentration (Cmax) of the drug in your bloodstream. These are measured in clinical studies where volunteers take either the generic or the brand-name version, and blood samples are taken over time. The goal? Make sure the ratio of the generic’s AUC and Cmax to the brand’s falls between 80% and 125%. If it does, regulators say they’re equivalent. That 80-125% rule has been around since 1992, when the FDA first laid it out. It’s now used everywhere - from the U.S. to Europe to India. But here’s the problem: this rule assumes the brand-name drug you’re comparing to is perfectly consistent. It’s not. And no one checks. A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that between-batch variability in the brand-name drug alone can account for 40% to 70% of the total error in bioequivalence studies. That means if you test one batch of generic against one batch of brand, you’re not measuring if the generic matches the brand - you’re measuring if it matches that one batch of the brand. And if that batch happened to be unusually strong or weak, your entire conclusion is wrong.What Happens When Batches Differ

Imagine two different batches of the same brand-name asthma inhaler. One batch delivers 10% more drug than the other. That’s not rare. It happens. Now, a generic manufacturer tests their product against the weaker batch. Their generic matches it perfectly - 95% of the AUC, 102% of the Cmax. It passes bioequivalence. But what if the next batch of the brand-name inhaler is the stronger one? Now your "equivalent" generic is delivering 15% less than what most patients are actually getting. That’s not bioequivalence. That’s luck. This isn’t theory. It’s been proven in controlled studies. When researchers tested multiple batches of the same reference drug, the point estimates for AUC and Cmax shifted dramatically - sometimes by more than 10 percentage points - just based on which batch they picked. That’s bigger than the entire 45% width of the acceptable range. And yet, regulators still approve generics based on single-batch comparisons.

Why the Current System Fails Complex Drugs

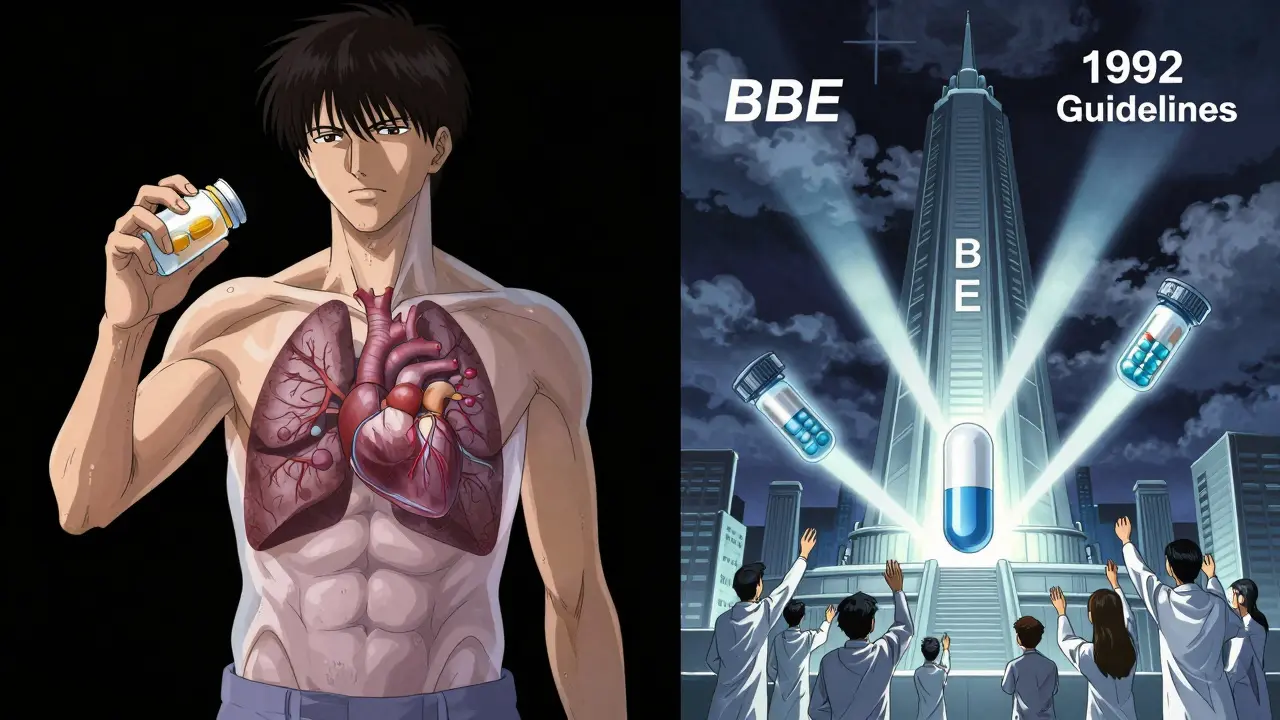

This problem gets worse with complex products - nasal sprays, inhalers, topical gels, injectables. These aren’t simple pills you can crush and dissolve. Their performance depends on tiny manufacturing details: particle size, spray pattern, viscosity, container material. A change in one step can alter how much drug actually reaches your lungs or bloodstream. The FDA’s own guidance on budesonide nasal spray acknowledges this. It says manufacturers should break down variability into "super-batch" differences and within-person differences. But that’s only for one drug. There’s no universal rule. And most generics aren’t tested this way. A 2021 paper in Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy proposed a better method: Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE). Instead of comparing the generic to a single reference batch, BBE compares it to the average variability of multiple reference batches. If the difference between the generic and the reference is smaller than twice the standard deviation of the reference batches, it’s considered equivalent. This isn’t just math - it’s common sense. If the brand’s own batches vary by 12%, then the generic should be allowed to vary by up to 12% too. But right now, the system forces the generic to match one snapshot of the brand, not the brand’s true range.What the Regulators Are Starting to Do

The industry is waking up. In 2022, the FDA reported a 22% increase in bioequivalence-related deficiencies in generic drug applications - many tied to poor batch characterization. That’s not because companies are sloppy. It’s because regulators are asking for more. The FDA’s draft guidance from June 2023, titled "Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies," is the first real signal that the rules are changing. It proposes requiring multi-batch testing for certain products and using statistical models that separate batch variability from other sources of error. The final version is expected in 2024. The EMA isn’t far behind. In 2023, their biostatistics working party identified "inadequate consideration of batch-to-batch variability" as one of the top three challenges in generic drug development. They’re now preparing to update their 2010 bioequivalence guideline with new requirements for batch selection and analysis. What’s changing in practice? Manufacturers are already adapting. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 78% of major generic makers now test at least three reference batches and two test batches for complex products - up from just 32% in 2018. That’s not because they want to. It’s because they have to, or their applications get rejected.

What This Means for You

You might think, "I just want my medication to work. Why does this matter?" Because if a generic drug is approved based on a weak batch of the brand, you might be getting less medicine than intended. That’s dangerous for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like blood thinners, seizure medications, or thyroid pills. A 10% drop in concentration could mean a clot, a seizure, or a thyroid crash. On the flip side, if a generic is rejected because it matches the strong batch of the brand, you might be denied access to a safe, effective, cheaper alternative. That’s not just a financial issue - it’s a health equity issue. The current system doesn’t protect patients. It protects the illusion of consistency.What’s Next? The Future of Bioequivalence

By 2025, experts predict that bioequivalence studies for complex generics will require at least three reference batches and two test batches. Statistical models will no longer treat batch variability as noise - they’ll treat it as a core part of the equation. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is also working on new guidelines under Q13 for continuous manufacturing - a shift away from discrete batches toward steady, uninterrupted production. That could eventually reduce batch variability altogether. But until then, the fix is in the data. Regulators are moving. Industry is adapting. But patients still don’t know the truth: the pill you’re taking might not be equivalent to the brand - not because it’s bad, but because the test that approved it was broken. The real question isn’t whether generics work. It’s whether we’re testing them right.What is the current acceptable bioequivalence range for generic drugs?

The standard acceptable range for bioequivalence is 80.00% to 125.00% for the ratio of geometric means of AUC and Cmax. This applies to most oral solid dosage forms under FDA and EMA guidelines. For highly variable drugs (CV >30%), the EMA allows widening the range for Cmax only, using scaled average bioequivalence (SABE), but AUC must still stay within 80-125%.

Why doesn’t bioequivalence testing account for batch variability?

Current guidelines were designed in the 1990s when manufacturing was assumed to be consistent across batches. Regulatory agencies focused on within-subject variability and treated between-batch differences as random error. But research since 2016 shows batch variability can make up 40-70% of total error. The system hasn’t caught up - yet. New draft guidance from the FDA and EMA now explicitly acknowledge this gap and are pushing for multi-batch testing.

What is Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE)?

BBE is a newer statistical method that compares the average difference between a generic and the reference drug to the natural variability seen across multiple batches of the reference drug. Instead of forcing the generic to match one batch, BBE asks: "Is the generic’s performance within the range of the brand’s own batch differences?" If the mean difference is less than twice the reference batch standard deviation, the products are considered equivalent. This method is especially useful for complex products like inhalers and nasal sprays.

Are all generic drugs tested with multiple batches?

No. For simple pills, most submissions still use a single batch of test and reference product. But for complex products - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams - regulators increasingly require at least three reference batches and two test batches. The FDA’s 2022 guidance on nasal sprays explicitly requires this. Industry adoption is rising: 78% of major generic manufacturers now use multi-batch testing for complex products, up from 32% in 2018.

How does batch variability affect patient safety?

For drugs with narrow therapeutic windows - like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin - even small differences in drug levels can cause serious harm. If a generic is approved against a weak batch of the brand, patients might receive too little drug and experience treatment failure. If it’s approved against a strong batch, a safer, cheaper generic might be wrongly rejected. Neither outcome protects patients. Multi-batch testing reduces these risks by ensuring the generic works across the full range of what the brand actually produces.

Ashley Porter

January 25, 2026 AT 16:49The 80-125% bioequivalence range is a statistical bandage on a systemic wound. We’re treating batch variability as noise when it’s the signal. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance is a start, but until we mandate multi-batch reference testing for *all* generics-not just complex ones-we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Henry Jenkins

January 27, 2026 AT 01:05Let’s be real-this isn’t just about regulatory inertia. It’s about cost. Testing three reference batches instead of one doubles the price of bioequivalence studies. Big pharma doesn’t care if your thyroid meds are 10% underdosed as long as the generic is cheaper than the brand. The system incentivizes the bare minimum. And now we’re surprised when patients have seizures or clots? We built this. We knew the gaps. We just didn’t fix them because it wasn’t profitable.

Nicholas Miter

January 28, 2026 AT 14:01my brother takes levothyroxine and switched generics last year. he went from feeling fine to exhausted, brain fog, weight gain. doc said 'it's the same drug' but i checked the batch numbers. the new one was approved against a low-potency batch of the brand. he switched back and boom-back to normal. this isn't theory. it's happening to people right now. the system is broken and no one's listening.

TONY ADAMS

January 30, 2026 AT 02:27why do we even bother with generics if they might not work? just make the brand cheaper lol

George Rahn

January 31, 2026 AT 16:25There exists within the annals of modern pharmacology a profound irony: the very institutions entrusted with safeguarding the health of the citizenry have, through bureaucratic complacency and statistical myopia, erected a cathedral of illusion-where equivalence is not measured by physiological truth, but by the arbitrary caprice of a 40-year-old regulatory algorithm. We are not merely tolerating risk-we are sanctifying it.

Ashley Karanja

February 1, 2026 AT 08:24I’ve been reading up on BBE and it’s honestly so intuitive it’s almost embarrassing we didn’t do this sooner. Like, if the brand’s own batches vary by ±12%, why should the generic be held to a ±25% standard? It’s like saying two different cars from the same model year must have identical engine torque, even though the manufacturer’s own production line varies by ±15%. We’re not testing equivalence-we’re testing luck. And the emoji? 🤦♀️ This needs to be mandatory, stat.

rasna saha

February 2, 2026 AT 05:00in india, we see this all the time. one batch of generic metformin works great, next batch gives me stomach cramps. doctors say 'it's the same' but we know better. i wish regulators here would catch up. patients are paying less but getting inconsistent results. it's not fair.

Skye Kooyman

February 3, 2026 AT 03:27the 80-125% range is a relic. multi-batch testing isn’t optional anymore. if you’re not testing at least 3 reference batches for anything complex, your application should get tossed. period.

James Nicoll

February 5, 2026 AT 00:37so the FDA says 'we’re updating guidelines' like that’s news. meanwhile, grandma’s warfarin dose is still based on a batch from 2019 that happened to be weak. congrats, we’ve turned medicine into a Russian roulette game with a 22% chance of losing. thanks for the innovation, guys.

shivam utkresth

February 5, 2026 AT 09:38BBE is elegant. it doesn’t demand perfection-it demands honesty. if the brand’s batches vary, why punish the generic for matching that variation? it’s not about being identical, it’s about being within the natural spread of what’s already accepted. this isn’t radical. it’s just… logical. and the fact that we need to spell this out says everything about how broken the system is.

Kipper Pickens

February 6, 2026 AT 15:45ICH Q13 and continuous manufacturing could be the real game-changer. If we move away from discrete batches entirely-steady-state production, real-time release testing-we eliminate the problem at the source. No more batch-to-batch chaos. Just consistent, reliable drug delivery. It’s not just better science-it’s the future. The question is, will regulators move fast enough to catch up before another patient gets hurt?