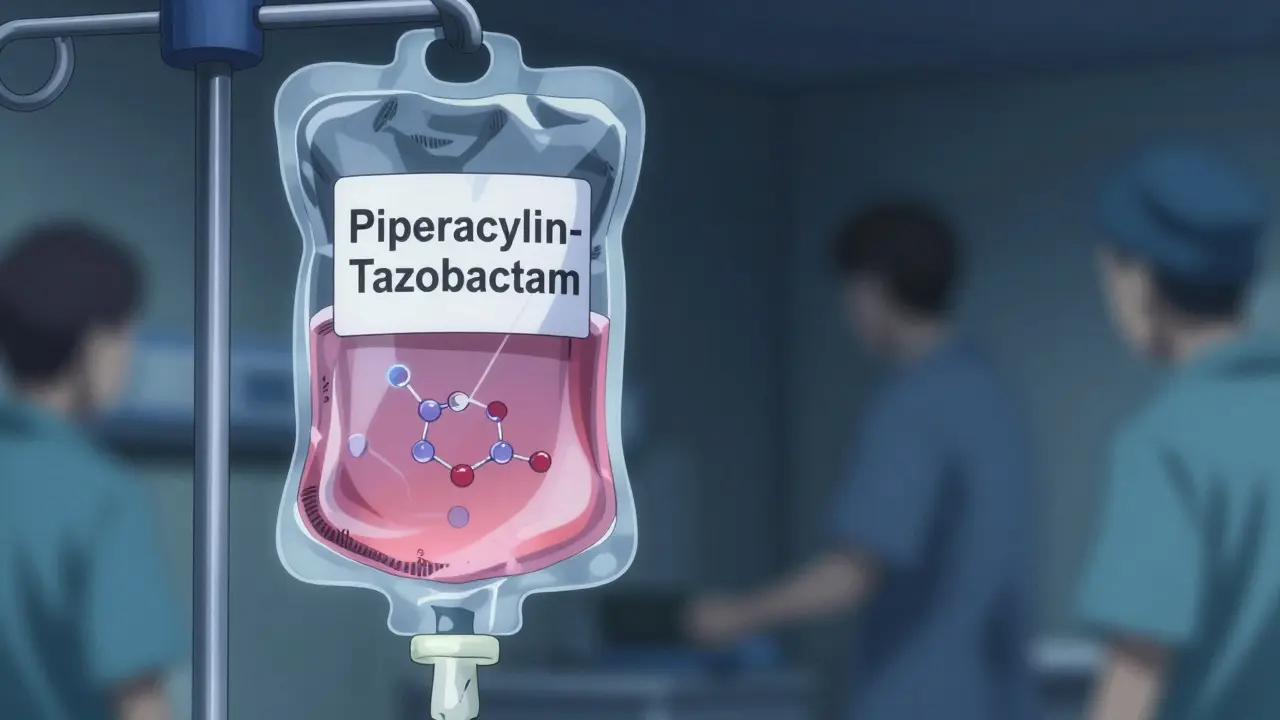

When you’re prescribed an antibiotic like piperacillin and tazobactam, you might not realize you’re getting a combination product - two drugs in one, designed to work better together than alone. These aren’t just random mixes; they’re carefully engineered to fight resistant bacteria, reduce treatment time, or simplify dosing. But here’s the real question: Can you get these same drugs for less? The answer is yes - and it’s changing how hospitals and clinics treat infections across the U.S.

What Exactly Are Antibiotic Combination Products?

Antibiotic combination products aren’t just two pills in one bottle. They’re FDA-approved formulations that combine two or more active ingredients - usually two antibiotics, or an antibiotic with a helper drug like a beta-lactamase inhibitor - into a single dosage form. Think of them like a team: one drug attacks the bacteria, the other disables the bacteria’s defenses. Piperacillin and tazobactam is a classic example. Piperacillin kills bacteria, but many bugs make enzymes that break it down. Tazobactam blocks those enzymes, letting piperacillin do its job.

Some combinations are co-packaged - like a vial of antibiotic paired with a syringe or pump - while others are pre-mixed in one container. These are called drug-device combination products, or g-DDCPs if they’re generic versions. The device isn’t just packaging; it’s part of how the drug is delivered. Think prefilled syringes, inhalers, or infusion pumps. The FDA treats these as one product, not two separate things.

How Do Generic Versions Become Available?

Brand-name antibiotic combinations are expensive because the companies that make them hold patents. Those patents usually last 20 years, but in practice, exclusivity often lasts 7-12 years due to delays and extensions. Once the patent expires, generic manufacturers can apply to the FDA for approval using the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) process.

Here’s the catch: Unlike a simple pill, a combination product - especially one with a device - can’t just copy the brand. The generic maker must prove it’s therapeutically equivalent. That means:

- The same active ingredients in the same strengths

- The same route of administration (IV, oral, inhaled)

- The same clinical effect - no more, no less

- The same safety profile

For drug-device combos, they also have to show the device works the same way. A prefilled syringe can’t leak. An inhaler can’t deliver uneven doses. The FDA requires detailed testing on form, function, and user interface. No clinical trials are needed - but the paperwork is intense.

The first major win came in 2010 when Hospira launched the first generic version of piperacillin-tazobactam for injection. That opened the door. Since then, more have followed - but not all.

Why Isn’t Every Combination Product Generic Yet?

Not every antibiotic combination has a generic version. Why? Three big reasons:

- Complexity - Combining a drug with a device makes approval harder. The FDA has to review both parts. Manufacturers need to prove every change in the device doesn’t affect safety or effectiveness.

- Cost - Developing a generic version of a combination product can cost millions. For drugs used in smaller populations (like rare infections), the return isn’t worth the investment.

- Regulatory confusion - The FDA assigns review to one center based on the Primary Mode of Action (PMOA). Is the drug the main part? Or the device? That decision changes the whole approval path and can delay things for years.

Even when a generic is approved, state laws can block pharmacists from substituting it for the brand. Most states allow substitution for single-drug generics - but not for combination products. Why? Because the laws were written decades ago, when most drugs were simple pills. Today’s complex formulations don’t fit that mold.

What Happens When Generics Hit the Market?

It’s not always a simple price drop and more prescriptions. A 2021 study in Nature Communications looked at 13 antibiotics after generics entered the market. The results were messy - and revealing.

Five antibiotics - aztreonam, cefpodoxime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and ofloxacin - saw prescriptions jump by 5% to over 400% in the year after generics launched. Why? In some cases, the drop in price made doctors more willing to prescribe them for less severe infections. In others, like aztreonam, a new inhalation treatment for cystic fibrosis launched at the same time, boosting demand for IV antibiotics used in preparation.

But cefdinir? Prescriptions dropped. Cefprozil and clarithromycin saw usage rise, but not because of price - likely due to changing guidelines or resistance patterns.

There’s no universal rule. Generic entry doesn’t automatically mean more use. It depends on the drug, the disease, the cost, and even what else is happening in the medical world at the same time.

How Much Money Do Generics Save?

Enough to change healthcare. Between 2010 and 2020, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $2.2 trillion. Antibiotic combinations contribute significantly to that.

When a brand-name combination drug costs $800 per dose and the generic is $150, the savings aren’t just for hospitals - they’re for patients too. Lower out-of-pocket costs mean fewer people skip doses or stop treatment early. That’s critical with antibiotics. Skipping doses breeds resistant superbugs.

One study found that when patients paid less, adherence improved by 18-22%. That’s not just a cost win - it’s a public health win.

What’s Next for Generic Antibiotic Combinations?

The FDA’s Office of Combination Products (OCP) is working to make approval smoother. In September 2024, they held a conference outlining best practices for developers. The message: we know these products are growing. We need better rules.

Experts are pushing for federal and state law updates to allow pharmacists to substitute generic combinations where proven equivalent. Right now, a pharmacist in Texas can’t swap a brand-name combination for a generic - even if the FDA says they’re the same - because state law doesn’t allow it.

Manufacturers are also learning. The six-phase development approach the FDA created for g-DDCPs is helping reduce delays. Companies are now designing devices with generics in mind from day one.

Looking ahead, expect more generic combinations - especially for common infections like pneumonia, UTIs, and skin infections. But progress will be slow. The science is solid. The system? Still catching up.

What Should Patients and Providers Know?

If you’re prescribed an antibiotic combination:

- Ask if a generic version is available - it’s often just as effective and much cheaper.

- Don’t assume the brand is better. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards.

- If your pharmacy won’t fill a generic, ask why. It might be state law, not safety.

- Report side effects or issues - even with generics. The FDA tracks safety through the same system.

For providers: Know the difference between a co-packaged product and a pre-mixed one. Know your state’s substitution rules. And don’t let outdated assumptions stop you from prescribing generics - they’re saving lives and money.

Are generic antibiotic combination products as effective as brand-name ones?

Yes. The FDA requires generic combination products to prove they are therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name version. This means they deliver the same amount of active ingredients, work the same way in the body, and produce the same clinical outcomes. No new clinical trials are needed - but manufacturers must submit extensive data on formulation, stability, and, if applicable, device performance.

Why aren’t all antibiotic combinations available as generics?

Some combinations are too complex to replicate easily, especially when they include a drug-device component like a prefilled syringe or inhaler. The approval process is expensive and time-consuming, and for drugs used in smaller patient groups, companies may not see enough return to justify the investment. Patent extensions and regulatory uncertainty also slow down generic entry.

Can a pharmacist substitute a generic antibiotic combination for the brand?

It depends on your state. Most states allow substitution for single-drug generics, but many don’t permit substitution for combination products - even when the FDA approves them as equivalent. This is because state substitution laws were written for simple oral pills, not complex drug-device combinations. Pharmacists may need a prescriber’s permission to switch.

Do generic antibiotic combinations cost less?

Yes - often dramatically. When generics enter the market, prices typically drop by 30% to 80%. For example, the generic version of piperacillin-tazobactam cost about 75% less than the brand. These savings benefit hospitals, insurers, and patients directly through lower copays and reduced overall treatment costs.

What’s the biggest barrier to wider use of generic antibiotic combinations?

The biggest barrier isn’t science - it’s regulation. Outdated state substitution laws, inconsistent FDA review pathways based on Primary Mode of Action, and the high cost of proving equivalence for device-integrated products all slow down access. Without legal and regulatory updates, even approved generics may not reach patients who need them.

Final Thoughts

Generic antibiotic combination products are one of the quietest breakthroughs in modern medicine. They don’t make headlines like new miracle drugs - but they save lives every day by making essential treatments affordable. The science is there. The savings are real. What’s missing is a system that lets them reach patients without unnecessary red tape. Until then, awareness and advocacy matter - whether you’re a patient, a pharmacist, or a doctor.

Frank SSS

December 31, 2025 AT 14:42So basically we’re paying $800 for a shot that’s basically the same as a $150 one? And the system’s still acting like it’s 1998? 😅

John Chapman

December 31, 2025 AT 15:00Generics saving billions? Yes please. I wish more people knew this stuff. Hospitals are literally throwing money away on brand names when the generic works just as well. Let’s get real here.

Paul Huppert

January 2, 2026 AT 11:22I’ve seen this in my clinic - docs still default to brand because they’re used to it. Patients don’t even ask. Sad.

Hanna Spittel

January 3, 2026 AT 15:39Wait… is this just Big Pharma’s way of keeping us hooked? 🤔💉 #conspiracy

Branden Temew

January 5, 2026 AT 13:54It’s funny how we’ll spend years debating whether a pill is ‘natural’ or ‘synthetic,’ but when a generic antibiotic saves a life and $650 per dose, we act like it’s some kind of magic trick. The system rewards complexity over common sense - and we call it innovation.

Why do we treat healthcare like a luxury product instead of a public good? Because we’ve outsourced morality to shareholders. The FDA says it’s equivalent? Good. The state says no substitution? That’s not science - that’s bureaucracy with a side of greed.

And yet, here we are, still pretending that if we just wait a little longer, the market will fix itself. No. It won’t. The market rewards patents, not people. The only thing that changes this is pressure - from patients, from nurses, from pharmacists who actually talk to the people taking these drugs.

Doctors need to stop being lazy. If a patient asks for the cheaper version, they should say ‘yes’ - not ‘let me check with legal.’ Legal isn’t the one holding the IV bag when the patient’s fever spikes.

And let’s not forget: skipping doses because you can’t afford the brand? That’s not patient noncompliance. That’s systemic failure. We call it ‘adherence’ like it’s a personal flaw, but it’s just economics dressed up in medical jargon.

Generics aren’t ‘second best.’ They’re the only thing keeping antibiotics alive. Without them, we’re one pandemic away from the 1920s. And yet, we’re still arguing over whether a prefilled syringe is ‘the same’ as another. The science says yes. The law says maybe. The patient says ‘I just want to live.’

So yeah. It’s not about the drug. It’s about who gets to decide what ‘good enough’ means. And right now? The answer is: not you. Not me. Not the person in the hospital bed. It’s the lawyer who wrote the state law in 1987.

Brady K.

January 5, 2026 AT 20:50Let’s be real - the FDA’s PMOA classification system is a bureaucratic nightmare. It’s like trying to classify a toaster that also makes coffee. Is it a kitchen appliance? A coffee maker? Who cares? Just let the damn thing work!

Manufacturers are now designing devices with generics in mind? That’s like saying ‘we’re gonna build a car with a manual transmission so someone else can copy it later.’ Why didn’t you think of that BEFORE you spent $200M on R&D?

This isn’t innovation. It’s regulatory theater. And we’re all paying for the performance.

Kayla Kliphardt

January 6, 2026 AT 15:55I’ve been on piperacillin-tazobactam. Generic worked fine. No issues. Just cheaper.

Joy Nickles

January 7, 2026 AT 23:04Wait… so you’re telling me the device… the syringe… the pump… the WHOLE THING… has to be EXACTLY the same? Like… the plastic? The color? The grip?!!! Are you kidding me?? That’s insane!! I mean… what if the generic has a slightly different texture?? Does that mean the bacteria can feel it?? 😭

Marilyn Ferrera

January 9, 2026 AT 00:14State laws need updating. Period. The FDA approves equivalence - state laws should reflect that. This isn’t about safety. It’s about inertia.

anggit marga

January 9, 2026 AT 10:01USA thinks it’s special but every other country just uses generics without drama. We’re so backwards it’s embarrassing. Why do we even have patents on medicine??

Retha Dungga

January 9, 2026 AT 15:17Maybe the real question is not if generics work… but if we deserve them 🌌

Emma Hooper

January 9, 2026 AT 22:03Generic antibiotics are the unsung heroes of modern medicine - the quiet ninjas of the IV bag world. No fanfare, no TED Talks, just saving lives and cash while the rest of us argue over the color of the syringe. Respect.

Urvi Patel

January 11, 2026 AT 00:24Why are we even talking about this? In India we just use the generic and move on. The fact that you need a PhD to understand why your IV bag costs 5x more is a sign of systemic failure. You guys really overthink everything